Imagine you’re sitting in the SAT exam hall. You’ve just bubbled in “B” for three questions in a row. As you move to the fourth question, you feel a slight pang of anxiety. It can’t be “B” again, right? You think. The odds of four “B”s in a row must be tiny. A “D” or an “A” is definitely “due.”

If this sounds familiar, you’ve just met one of the most common “glitches” in the human brain. Whether you’re staring at an OMR sheet or a roulette wheel, your intuition is likely falling for the Gambler’s Fallacy. Today, we’re going to deep dive into why our brains crave patterns—and how the Law of Large Numbers is the cold, hard math that actually rules the world.

The Night Millions Vanished: The Monte Carlo Story

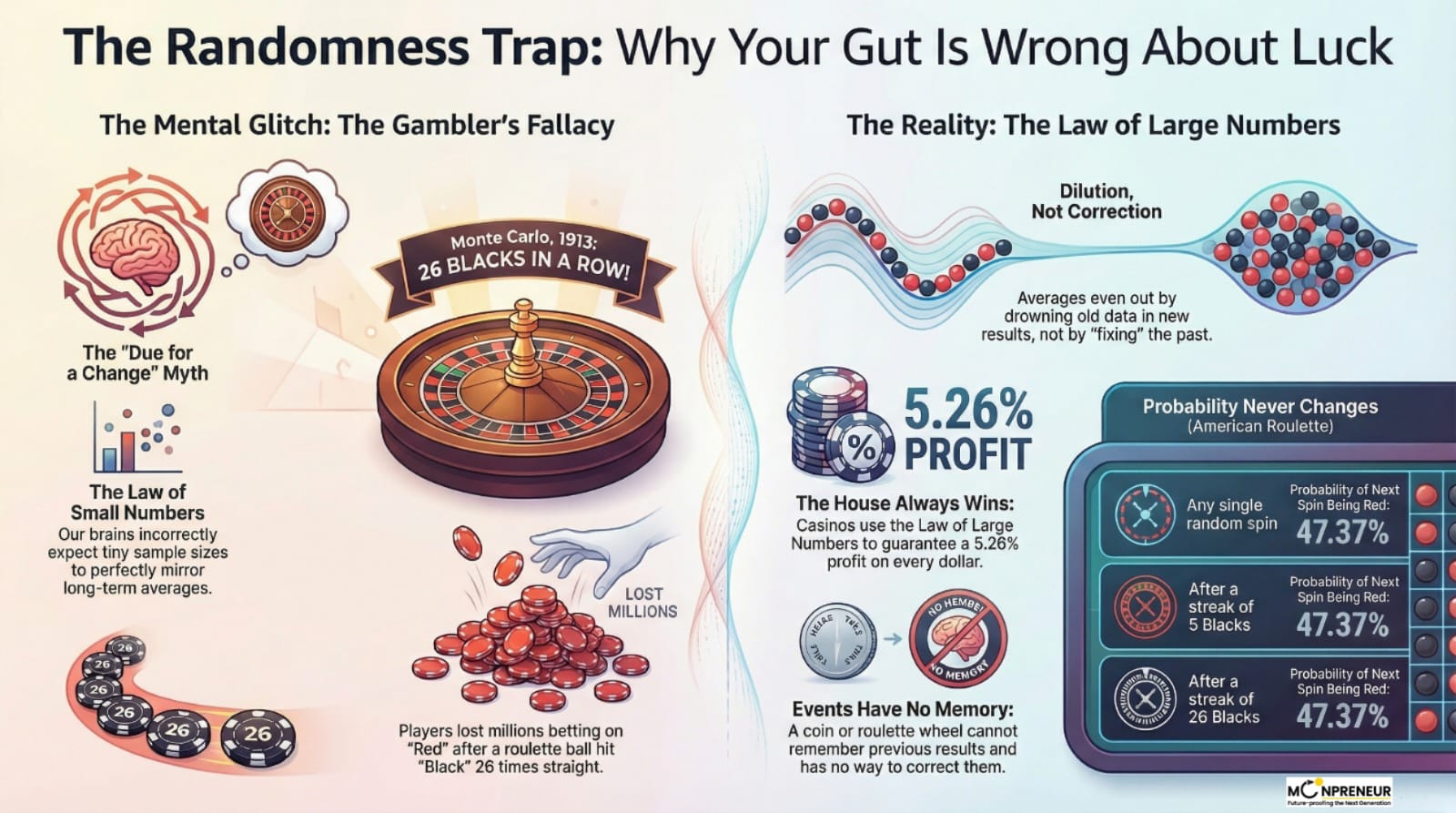

To understand these concepts, we have to go back to a hot summer night in 1913 at the Monte Carlo Casino. A roulette ball landed on black. Then black again. Then black a third time. By the time it happened ten times in a row, the air was electric.

The crowd was certain: Red was “due.” They started shoveling money onto red, convinced the universe had to balance things out. But the ball landed on black again. And again. It happened 26 times in a row. By the time the streak finally broke, millions of francs had vanished into the casino’s vaults.

The players weren’t stupid; they were just human. They were victims of the Gambler’s Fallacy: the deep-seated belief that past random events can somehow affect future ones.

The Gambler’s Fallacy (The “Memory” Myth)

If observing a series of random events, say the flipping of a fair coin, and we note that the last two tosses resulted in heads, we may expect ( incorrectly due to a misinterpretation of the law of large numbers) that the next flip of the coin will result in tails. As we know, a fair coin has a 50% chance on each flip to land on heads or tails; therefore, for any given set of trials, the results should be evenly split between the two outcomes.

The issue is that no one told the coin. The coin flip result is the result of the many small variations that occur to find it’s landing position. It has no memory or does not consider the tally of previous flips. It is just flying through the air and landing on one side or the other based on this one trial.

With a run of say 5 tosses resulting in heads, there is a 1/32 chance of that occurring. The chance of the next toss being heads or tails remains unchanged; it is 1/2 heads and 1/2 tails. We may wish the result to be tails given the run of 5 heads, yet that is only our belief, not the probability.

If we repeat the experiment of tossing a coin five times many times (many being a large number – say thousands or millions of 5-toss experiments), the result on average would be 2.5 heads per group of five tosses. For any single toss, the result is unknown with an equal chance of a head or tails, whether the first toss or the 1 millionth. None of the many trials provides any information about the results of the sixth toss other than that it remains 50/50.

Why do we fall for it?

Psychologists like Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky found that humans are “pattern-seeking machines”. We use something called the representativeness heuristic—a mental shortcut where we think a small sample (like 5 coin flips) should perfectly mirror the 50/50 long-term average. Tversky called this the “Law of Small Numbers,” which is actually a sarcastic name for our brain’s mistaken belief that tiny samples represent the whole.

The Law of Large Numbers (The Long Game)

The law of large numbers is a theorem in probability theory that states that as the number of trials in an experiment increases, the average of the results will get closer and closer to the expected value. In other words, the law of large numbers says that if you repeat an experiment many times, the results will tend to average out.

For Example: If you flip a coin 10 times, you might get 8 heads (80%). But if you flip it 10,000 times, you are almost guaranteed to be very close to 5,000 heads (50%)

What People Get Wrong:

The most common misconception here is that the law of large numbers guarantees that you will eventually get the expected value. This is not true. The law of large numbers only says that the average of the results will converge towards the expected value as the number of trials increases. It does not guarantee that you will ever get the expected value, especially for any finite number of trials (even if that finite number of trials is extremely high). This is what leads to the Gambler’s Fallacy. The law of large numbers only makes predictions on the convergence of infinitely many experiments- it can’t be used to make predictions about a specific experiment.

If you start with 10 tails in a row, the universe doesn’t “force” 10 heads to happen next to even things out.

Instead, the LLN works through dilution, not correction. Those 10 initial tails become a “totally insignificant little blip” when they are drowned out by a million future flips that behave normally. The past isn’t balanced; it’s just overwhelmed by an ocean of new data.

Example:

Scenario: 10 consecutive coin tosses land on heads.

- Gambler’s Fallacy: Believing tails is “due” on the 11th toss. This is false; the probability remains 50/50.

- Law of Large Numbers: The 10 heads represent a small, extreme sample. Over 10,000 more tosses, the 10 heads will become statistically insignificant, and the total ratio will move toward 50/50.

Why This Matters for Your SAT (and Life)

For an SAT student, understanding these two concepts is like having a superpower for your nerves:

- Trust the Data, Not the “Streak”: If you’ve calculated an answer and it’s “C” for the fourth time, don’t change it just because it “feels” wrong. Each question is an independent event.

- Sample Size Matters: When you see a “finding” in a Reading passage based on a survey of 10 people, your “Law of Large Numbers” alarm should go off. Larger sample sizes provide more reliable estimates of a population.

- Avoid the Hot-Hand Fallacy: Just as we think a “losing” streak must end, we often think a “winning” streak will continue (like a basketball player who can’t miss). Both are illusions. Past success in random or near-random trials doesn’t guarantee the next one.

The Bottom Line

The casino wins because its entire business is built on the Law of Large Numbers. They know that while one player might get “lucky” in the short term, the math guarantees the house will win over thousands of spins. Don’t let your brain weaponize a “glitch” against you. Stick to the logic, trust the math, and keep your eyes on the long-term average.

Want to excite your child about math and sharpen their math skills? Moonpreneur’s online math curriculum is unique as it helps children understand math skills through hands-on lessons, assists them in building real-life applications, and excites them to learn math.

You can opt for our Advanced Math or Vedic Math+Mental Math courses. Our Math Quiz for grades 3rd, 4th, 5th, and 6th helps in further exciting and engaging in mathematics with hands-on lessons.

Recommended Reading:

- Solving Exponential Equations Using Recursion: A Step-by-Step Guide

- Linear Equation – One Solution, No Solution and Many Solutions

- Interesting Geometry Problem to Solve For Kids

- Application & Proof of the Sherman-Morrison-Woodbury Identity

- The Geometry Problem That Still Defeats ChatGPT, Gemini, and Grok